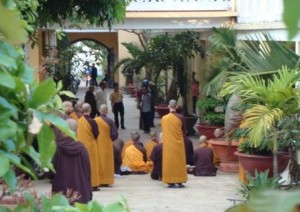

Buddhist Monks blocked the raid of public security agents during the visit of the EU-Delegation at Phuoc Hue Pagoda, Lam Dong Province, on 9 Dec 2009

Buddhist Monks blocked the raid of public security agents during the visit of the EU-Delegation at Phuoc Hue Pagoda, Lam Dong Province, on 9 Dec 2009

Joint Statement of Concern on Vietnam’s Draft Law on Religion

We, the undersigned civil society organizations are concerned that Vietnam’s draft Law on Belief and Religion[i] is inconsistent with the right to freedom of religion or belief. We call upon the Government to comprehensively revise the draft Law to conform with Vietnam’s obligations under international human rights law in the course of an inclusive consultation process with recognized and independent religion or belief communities within Vietnam and human rights law experts, including the UN Special Rapporteur on the right to freedom of religion or belief.

In its current form, the draft Law places limitations on freedom of religion or belief that extend beyond those permitted under international human rights law that is binding on Vietnam.

Article 18(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), to which Vietnam is a state party, requires the authorities to ensure that the freedom to manifest one’s religion or belief is subject only to such limitations as are prescribed by law and are necessary and proportionate to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others.

While the draft Law purports to acknowledge “the right to freedom of religion and belief” and proclaims that the “government respects and protects the freedom of religion and belief of everyone,” the provisions of the draft Law, if passed, would act as a powerful instrument of control placing sweeping, overly broad limitations on the practice of religion or belief within Vietnam, perpetuating the already repressive situation.

The UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, Dr. Heiner Bielefeldt, summarized his observations of the situation of religion or belief in Vietnam following a visit to the country in July 2014 saying, “Whereas religious life and religious diversity are a reality in Viet Nam today, autonomy and activities of independent religious or belief communities, that is, unrecognized communities, remain restricted and unsafe, with the rights to freedom of religion or belief of such communities grossly violated in the face of constant surveillance, intimidation, harassment and persecution.”[ii]

We note the following concerns, among others, with the draft Law[iii] which are illustrative of the many provisions that are inconsistent with Vietnam’s obligations under the ICCPR including the obligation to respect and protect the right to freedom of religion or belief:

1. Onerous requirements of registration

The draft Law places onerous requirements of registration on “religious organizations”.

The system of “you request, we may grant”[iv] set out in provisions throughout the draft Law demonstrates a serious misunderstanding of the government’s role with respect to protecting the right to freedom of religion or belief under international law. As stated by the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief in his aforementioned report, the exercise of religious freedom or belief is an universal right which “cannot be rendered dependent on any particular acts of administrative approval”.[v]

2. Excessive state control over and interference in religious organizations’ internal affairs

The draft Law is marked throughout by provisions that, if adopted would empower the Government to intrusively monitor and “intervene in the internal affairs and administration” [vi] of “religious organizations”.

This takes the form of government interference and control over appointed leadership, pedagogy and content of religious training, as well as unreasonable notification requirements of organizational changes in personnel or bylaws subject to State approval. In addition, a clause stipulating that Vietnamese history and law should be a main subject in training materials allows the authorities to interfere with the content of religious education. These provisions are inconsistent with the requirement under international law that limitations imposed on the right to freedom to manifest one’s religion or belief be strictly necessary and proportionate to one of the aims set out in article 18(3) of the ICCPR.

3. Overly broad and ambiguous language which may facilitate discrimination

Cases of discrimination by the State against minorities whose cultural and religious practices are considered to be “outside” the mainstream national narrative are well documented.[vii]

The draft Law contains overly broad and ambiguous language that, in addition to the other abuses that frequently arise from imprecision in laws that define the enforcement authority of government entities, could be used to perpetuate discrimination against ethnic and indigenous minorities, independent groups and those whose religion or belief is seen as “foreign” in favour of religious entities recognized by the Communist Party.[viii] For example, the draft Law gives the authorities power to suspend religious festivals or delay conferences or congresses in the name of “national defence or security, public order, social order, or public health” and suspend organizations that are deemed to have carried out “forbidden acts,” including causing harm to “national defence and security, public order, and morality.”

At a minimum, restrictions on religious activities that are not among the limitations permitted under Article 18(3) of the ICCPR, such as those designed to preserve “social order” or to prevent ‘sully[ing] the image of national heroes and notables” , must be removed. Other restrictions, such as those deemed necessary to “national defense and security” and “public order”, must be carefully reviewed to ensure both that religious activities are not restricted more rigorously than similar activities conducted for non-religious reasons and that any suspension of a religious festival or delay of a congress or conference is strictly necessary and proportionate to meet one of the permissible aims set out in article 18(3) of the ICCPR.

Furthermore, as recommended by the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief in his report concerning his visit to the country last year, “Effective and accessible legal recourse must be prioritized in current legal reforms in order to allow victims, whose freedom of religion or belief have been infringed upon, to obtain effective redress and compensation within an independent judicial system and judiciary”.[ix]

In light of these and other concerns about the current draft of the Law, we make the following recommendations to the Government of Vietnam:

- Revise the draft Law in a manner consistent with Vietnam’s obligations under article 18 of the ICCPR to guarantee absolutely the internal dimension of the right to freedom of religion or belief.

- Revise the draft Law in a way that ensures that the practice of religion or belief in Vietnam is not conditional upon a process of state recognition, registration and approval.

- Remove all articles that interfere in the internal affairs and administration of religious organizations including those that prescribe that the content of teachings on religion or belief include Vietnamese history and law.

- Remove references such as those to “social order” and “sully[ing] the image of national heroes and notables” as reasons for placing limitations on freedom of religion or belief in the draft Law, as well as other language that is inconsistent with Article 18 of the ICCPR.

- Ensure that any limitations placed on the manifestation of religion or belief comply with Vietnam’s international legal obligations, in particular the permitted limitations as set out in article 18(3) of the ICCPR, and specify that any restrictions on such grounds must be both necessary and proportionate to the particular aim.

- Remove all overly broad and ambiguous language, including that which could be arbitrarily interpreted and result in discrimination or other violations of human rights against ethnic minority and independent religious or belief groups, and favoritism towards recognized, state-controlled or state-friendly groups.

- Include in the draft Law a legal framework that sets out effective and accessible legal avenues for victims of discrimination or other violations of human rights to obtain remedies and reparation in accordance with international law and standards.

- Ensure the draft Law is also consistent with Vietnam’s obligations under the ICCPR to guarantee the rights to freedom of expression, freedom of association, freedom of assembly and privacy.

- Explicitly guarantee in the draft Law the legal precedence of international human rights instruments to which Vietnam is a state party, which appeared in earlier drafts and has been regrettably dropped.

- In the process of redrafting the Law, consult the UN Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief and other experts in international human rights law, as well as those who will be affected by the Law, including religion or belief communities within Vietnam, during the drafting process

Endorsing Organizations:

- The Alternative ASEAN Network on Burma (Altsean Burma)

- Amnesty International

- Boat People SOS (BPSOS)

- Cambodian Center for Human Rights

- Cambodian Human Rights and Development Association (ADHOC)

- Cambodian League for the Promotion and Defense of Human Rights (LICADHO)

- Campaign to Abolish Torture in Vietnam (CAMSA)

- Christian Solidarity Worldwide

- Christian Solidarity Worldwide – USA

- Civil Rights Defenders

- Coalition for a Free and Democratic Vietnam

- Danish Mission Council

- Freedom House

- International Commission of Jurists (ICJ)

- International Institute for Religious Freedom

- Khmer Kampuchea Krom for Human Rights and Development Association (KKKHRDA)

- Lantos Foundation for Human Rights & Justice

- People Serving People Foundation (PSPF)

- People’s Empowerment Foundation (PEF)

- Release International

- Smile Education and Development Foundation

- Society for Threatened Peoples International

- Stefanus Alliance International

- VETO! Human Rights Defenders’ Network (VETO!)

- Vietnam Committee for Human Rights

- Voice of Martyrs Canada

- Voice of Martyrs Korea

Download pdf file here: 00-Joint Statement on Vietnam Draft Law on Religion 3Nov2015

Download Vietnamese Version here:

00-Tuyên Bố Chung về Dự thảo Luật Tôn giáo Việt Nam (VN)-3Nov2015

NOTES

[i] This statement refers to the content of Draft 5 of the draft Law which was circulated in September 2015. In April 2015, the Vietnamese government made public a draft Law on Belief and Religion (draft 4) which attracted criticism and concern from various religious communities including: the Interfaith Council of Vietnam; the Vietnamese Conference of Catholic Bishops; the Kontum Diocese, Bac Ninh Diocese and Vinh Diocese of the Vietnamese Catholic Church; the Independent Hoa Hao Buddhists; and Cao Dai, Buddhist and Protestant communities. A wide range of statements can be found at: www.dvov.org/2015/10/26/vietnamdraftlor/

[ii] UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, Heiner Bielefeldt, UN Doc. A/HRC/28/66/Add.2 (30 January 2015), summary page 1.

[iii] For a more detailed analysis of the draft Law, please see the following: www.csw.org.uk/2015/05/15/report/2587/article.htm and www.worldwatchmonitor.org/2015/05/3844615

[iv] Observations and Input Related to the Fourth Draft of the Law on Religion and Belief, Bishop’s Court of Vinh Diocese, www.dvov.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Vinh-Diocese-Comments-on-Draft-Law-on-Religion-05-03-15.pdf

[v]UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, Heiner Bielefeldt, UN Doc. A/HRC/28/66/Add.2 (30 January 2015), para 82.

[vi] Statement of independent Hoa-Hao Buddhists regarding the 4th draft Law on Religion and Belief, www.dvov.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Statement-of-independent-HoaHao-Buddhists-regarding-Draft-Law-on-Religion.pdf

[vii] See, e.g., Human Rights Watch, Persecuting “Evil Way” Religion: Abuses against Montagnards in Vietnam (2015) [hereinafter cited as “Evil Way” Religion], https://www.hrw.org/report/2015/06/26/persecuting-evil-way-religion/abuses-against-montagnards-vietnam (documenting the persecution of Montagnard Christians).

[viii] “The current persecution is being carried out against what Vietnamese authorities call “objects” (doi tuong) of security force suspicions. These include those who subscribe to beliefs the Vietnamese government maintains are “set up by the reactionaries” to oppose Communist Party rule and achieve other “dark purposes,”[3] such as to “abuse the freedom of belief to sow division among the national great unity.”[4] “Evil Way”Religion, supra note 7. See also Christian Solidarity Worldwide, Vietnamese Christian Villagers Pay a High Price (2013), http://www.csw.org.uk/2013/04/18/news/1434/article.htm: “Pressure to recant does not only come from the authorities. One Vietnamese pastor told us that new Christians’ friends and family also try to discourage them from going to church, telling them that Christians follow a “foreign religion” linked to the CIA.”

[ix] UN Human Rights Council, Report of the Special Rapporteur on freedom of religion or belief, Heiner Bielefeldt, UN Doc. A/HRC/28/66/Add.2 (30 January 2015), para 83(i).